‘Iacta alea est’

Sew for Static Elegant Websites

When I first came across Mote I was inspired by its simplicity. At the time I was fighting Jekyll configuration and plugins for building a multi-lingual website for a friend. After scribbling down some notes on a piece of paper I came up with Sew, a tool for stitching together static, elegant websites.

I’d never even dreamed of building my own static site generator, but something about seeing how simple code could be after conversing with Michel Martens and checking out his code triggered me to give it a go. I had a mental block that these things were beyond my grasp and capability. I was encouraged, even given permission—as funny as that sounds—to build a tool that was formed for my particular use case rather than trying to bend a bigger, more complex tool to fit something it wasn’t quite designed for.

I was pretty amazed at what I could accomplish in a short space of time and with such a small amount of code—the library weighs in at 84 SLOC. It is built on the Mote templating library which is the only external dependency outside of the Ruby Standard Library.

Of course it is not as fully featured as Jekyll or Middleman but really that’s the point. Similar to Rails, these static site generators reward the golden path but become difficult once you step off.

Mr. Martens taught me to think a lot more before committing to code. That code is simply the expression of an idea, and if your thoughts are clear and the mental models fit then writing the code is the easiest part. The difficult part is then deciding on your approach. You can see that in Seg and Syro, they both embody a simple idea at their core—path segments and tree-oriented routing respectively—and are built around that idea. Nothing more, nothing less.

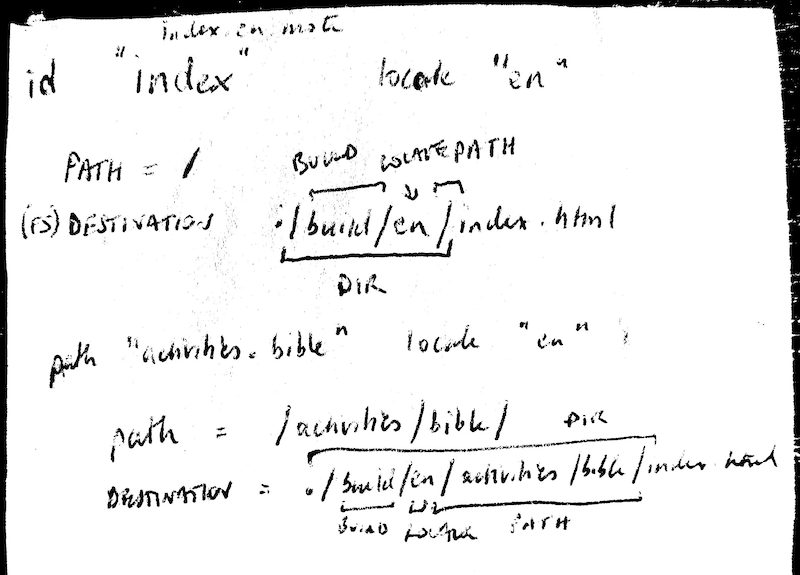

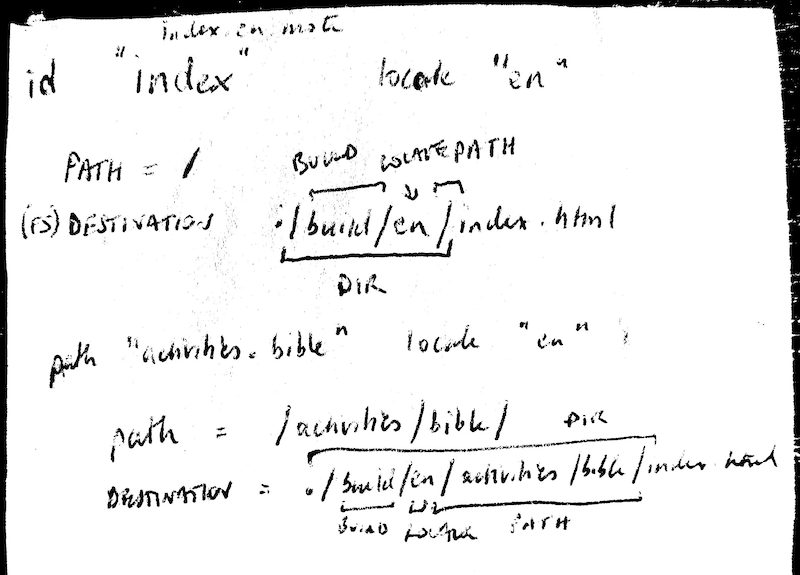

I jotted down some notes on paper:

When you consider the problem more deeply a static site generator is nothing other than a transformation of data located in a directory of files from one form to another. The fact that it is the file system muddies the waters a little, but if you imagine that to be its own data structure it becomes clearer. A site is a set of pages and each page has a set of attributes. Each page stores its attributes in both YAML frontmatter and the file body. If you flatten that down then the body becomes simply an additional attribute in the frontmatter.

When you consider the problem more deeply a static site generator is nothing other than a transformation of data located in a directory of files from one form to another. The fact that it is the file system muddies the waters a little, but if you imagine that to be its own data structure it becomes clearer. A site is a set of pages and each page has a set of attributes. Each page stores its attributes in both YAML frontmatter and the file body. If you flatten that down then the body becomes simply an additional attribute in the frontmatter.

---

title: About

---

<h1>About</h1>

<p>Hello</p>

is the same as:

{

title: "About",

body: "<h1>About</h1>\n<p>Hello</p>"

}

Now there is also a set of potential data that is not in the file, but is contained with the file, in the file name. This is something I freely took advantage of in my design. The above contents would be placed in a file with name about.en.mote. So we can add two pieces of information to our page data:

{

id: "index",

locale: :en,

title: "About",

body: "<h1>About</h1>\n<p>Hello</p>"

}

From this basic set, which is a transformation of the data found encoded in the file(s) to a Ruby structure, we can then work to transform the data into the output of the site, a set of HTML files.

We can calculate some additional fields based on a default build directory of build:

{

id: "index",

locale: :en,

title: "About",

body: "<h1>About</h1>\n<p>Hello</p>"

path: "/about/"

destination_dir: "/build/en/about/",

destination: "/build/en/about/index.html"

}

The only other transformation that then needs to take place is the rendering of the page body together with the data and finally writing the rendered output to the HTML file at the destination.

It’s painfully simple when you break the problem down and model it correctly. When you have the initial model, you are free to take the design in different directions as desired. For example I made the conscious decision to keep everything in one folder versus distributing the files across different folders. Nesting is done on the basis of the file path, e.g. about.team.en.mote would yield /en/about/team/index.html. This also keeps the pages for different locales together in the file system, rather than breaking them up:

about.team.de.mote

about.team.en.mote

about.team.es.mote

about.team.fr.mote

about.team.nl.mote

index.de.mote

…

And of course, it goes without saying that locale support is baked in. I don’t have to fiddle with the innards of another tool, it has first-class support. Things that should be simple to do with locales, are simple. I can easily retrieve the corresponding page from a different locale by searching the list of pages on id and locale. If I want the path to be localised I can include that in the frontmatter.

Now this static site generator won’t take the world by storm. I don’t even expect anyone to use it except for myself. But it fits. It fits my use-case. And more than that, I can easily “hack” it to do anything I want it to do because the model and core is so minimal that it doesn’t stand in my way.

For me, it showcases the power of boiling down a problem to its essence, and having the confidence to overcome the barrier that such simplicity affords. We often feel like our tools should be complex. If they are not complex then they can’t be ‘good’ tools. That’s the inner monologue. No doubt, as the use-cases increase, so does the complexity, but even doing this exercise has taught me more about Jekyll or Middleman than reading their source code ever would. So it’s not a zero-sum game.

What are the tools that you fight with? Have you ever tried to boil the problem down to first principles? Have you ever tried to rewrite those tools yourself? You might be pleasantly surprised.

—Sunday 21st February 2021.

When you consider the problem more deeply a static site generator is nothing other than a transformation of data located in a directory of files from one form to another. The fact that it is the file system muddies the waters a little, but if you imagine that to be its own data structure it becomes clearer. A site is a set of pages and each page has a set of attributes. Each page stores its attributes in both YAML frontmatter and the file body. If you flatten that down then the body becomes simply an additional attribute in the frontmatter.

When you consider the problem more deeply a static site generator is nothing other than a transformation of data located in a directory of files from one form to another. The fact that it is the file system muddies the waters a little, but if you imagine that to be its own data structure it becomes clearer. A site is a set of pages and each page has a set of attributes. Each page stores its attributes in both YAML frontmatter and the file body. If you flatten that down then the body becomes simply an additional attribute in the frontmatter.